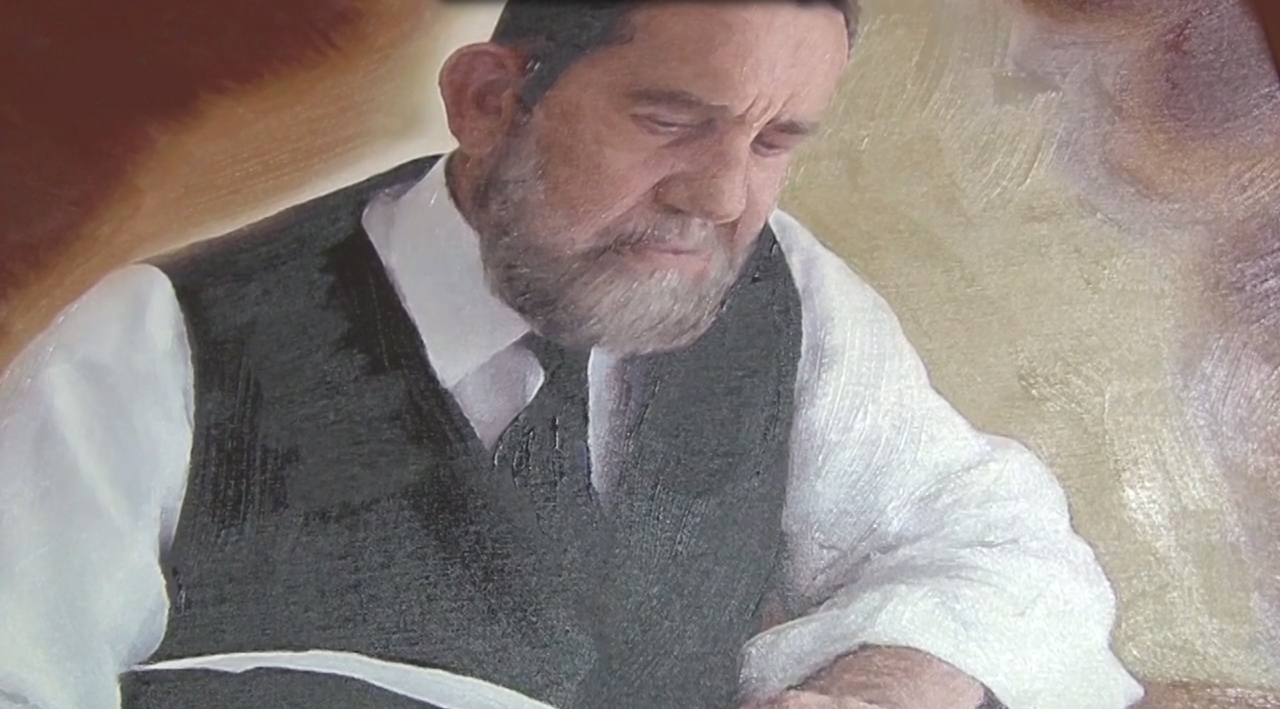

Father Bedros – A patriot and rebel

On January 26, 2014 and at the age of 77 the well-known Assyrian priest Bedros Shushe passed away in Germany. Father Bedros was a remarkable priest of the Syrian Orthodox Church. He was interested neither in power nor in wealth. Instead, he was a patriotic rebel who encouraged the Assyrian people to stand up against the mismanagement of the church leadership and abuse of power, writes journalist Augin Kurt Haninke.

Commonly known as Qasho Bedros, this brave man stood upright during his entire life, while facing constant attacks from church leaders and various civilian actors for his outspokenness and reformist zeal that is very rare among our clergy. His goal was to unite the church and the nation in the struggle for survival of the vulnerable Assyrian nation. But the opposition was overwhelming and forced him to escape his unjustly acting church leadership and join the Catholic Church from 1991 until 2005. The resistance was carried out by reactionary forces, mostly mighty clans from his birthplace Midyat. Those clans cooperated with the Church’s leadership in fighting the progressive ideas of the Assyrian national movement in the European diaspora. In the Syrian Orthodox Church, this struggle began with the late patriarch Afrem Barsom (p.1933-1957) and continues until today under the guise of so-called ’name conflict’.

Who was this upright priest?

Bedros Shushe was born in Midyat in 1937; his poor Assyrian parents were traumatized as all the survivors who tried to recover from the genocide (Seyfo) of 1915. A new era begun in Turkey’s history with Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s new republic in 1923 characterized by the state effort to assimilate ethnic minorities to become Turks. An important step in this policy of assimilation was to ban all teaching outside the Turkish education system. The official Assyrian schools were closed in 1928. In Midyat there were previously four schools in the churches directed by teachers exempt from military service and paid by the state. In 1934 Turkey issued a new edict of assimilation when the law on Turkish surnames came into force. All citizens were forced to adopt a Turkish surname and all Assyrian towns and villages got Turkish names too. The project was launched during a period of two years and the family of Shushe got the Turkish surname Öğünç.

The Assyrians in Turabdin continued to provide their children with education in their own language, but under the guise of ”Bible study”. When the young Bedros was about 6 years, he began to learn his native language in these schools, while he was visiting the Turkish elementary school. At the age of 16, he was appointed teacher to the Assyrian village of Hah, from where his family had moved to Midyat about 250 years earlier. A year later, he was assigned as a teacher in St. Shmuni Church in Midyat, where he remained for 15 years. His assignment was in 1955, few years after Afrem Bilgiç from the village Bote became the new bishop (1952) of Turabdin. Malfono[1] Bedros distinguished himself from his predecessors by his reformist push with respect to his church’s traditions. For example, he was the first in Turabdin’s history who formed a girls’ choir participating in regular Sunday Masses. According to chorepiscopos Kerim Asmar, a pupil of Bedros residing in Switzerland, the girls were even allowed to read Paul’s epistels to the congregation. According to Abdulmesih BarAbraham, another pupil of Malfono Bedros, he taught hundreds of children of all ages, including some 30 girls. He structured the classes according to levels; advanced students taught the entry classes. Another ”novelty” by him was to let students play theatre at New Year and other holidays, which was about the seasons or the biblical story of Joseph in Egypt. To do that, he had all the time support of his mentor bishop Afrem in Midyat says BarAbraham.

Eventually, he also learned English spontaneously and began teaching it. Even Muslim pupils from the district of Estel used to be taught by him English. He received five Turkish lira per pupil and month – a welcome addition to a modest teacher’s salary that was not even enough for an apartment of his own, says father Bedros in a long interview with Jan Beth-Sawoce from 2001. He further tells, that he got some help from a woman named Bahija in Midyat who knew English well. But for the major part he learned as autodidact through the study of Turkish-English books.

At this time, in the 1950s and 1960s, Malfono Bedros knew not much about his Assyrian roots, although many church songs were glorifying Beth-Nahrin (Mesopotamia). Almost no one else in Turabdin was aware of his ethnic origin or his Assyrian ancestors prior Christianity, because the church had since long time considered its ancient history as pagan and distanced itself from the pre-Christian heritage. But in 1967-68, Malfono Bedros says, that he received a unique book sent to him by mail. The author was living in Brazil and was the late Malfono Abrohom Gabriel Sawme. Gabriel Sawme was a former student of Yuhanon Dolabani (the later Bishop of Mardin) at the famous Assyrian school in Adana in the early 1920s. The book was called Kthobo d mardutho d Suryoye (published in 1967) and described in details the Assyrian history, such as how Christianity is based on our Assyrian ancestral faith and what great things they had done in the service of humanity. This laid the foundation for the patriotism Malfono Bedros wanted to transfer to a lost church which rejected its honorable ancestors.

Beside many years of teaching, Malfono Bedros has also made an important contribution to the language. With his beautiful handwriting he has copied a few hundred ecclesiastical books that have been used in many churches and monasteries in Turabdin or elsewhere. Ancient scripts that were used in the liturgy were torn hard and it was not always easy to repair those. In the absence of printing Malfono Bedros sat down and wrote them page by page, day in and day out. Even the ink was scarce. According to BarAbraham, he produced even his own ink based on toasted wheat and other natural ingredients. I have seen some books with my own father’s handwriting, written in wheat-based ink. It has a beautiful dark brown color and does not fade so easily. Malfono Bedros not only copied the texts of the old books. He also took care of the binding of the new books before handing them over to the clients. Even after he arrived in Germany, he has continued copying books using the old Syrian script. Overall, and according to BarAbraham, Mafono Bedros produced more than 300 books and booklets in his own handwriting.

In 1969 Bedros Shushe came to Germany as guest worker. But one of his old friends from his time in Midyat, the orientalist Helga Anschütz, felt that his knowledge and expertise would be better put to use if he was both a priest and a kind of social advisor to the new Assyrian guest workers. Her contacts within the Catholic Church in Bavaria led to the local bishop and other potentates who suggested this to the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch Yakub III in Damascus. The Patriarch accepted the proposal and in 1971 Malfono Bedros was ordained as priest by Bishop Afrem in Midyat. The Catholic aid organization Caritas began to employ Father Bedros, who became the only Assyrian priest for the whole Central Europe (Germany, Switzerland, Austria etc). For nearly a decade, he came to spend a large part of his life in rail and car travel between different locations. At that time there were no telephones in most guest worker’s homes. As Malfono Aziz Hawsho, another pupil of his living in Germany in the early 1970s tells, Father Bedros used to write letters or postcards and announce his arrival. The same did the scattered parishioners when they had a child to baptize or another religious service.

As the immigration of Assyrians to the European countries increased towards the end of the 1970s, other Assyrian priests were stationed in Germany and other countries. Many of our priests are known for their desire for power and money. In Turabdin both priests and parishes were poor. Assyrian priests had no salary, but lived on contributions from the congregation. But in Germany and Switzerland church members were well-off compared to their brethren in the homeland. Thus, it was very attractive for a priest to be stationed in Germany or other European countries. This meant that some priests and monks in their rivalry began to intrigue against Father Bedros, even though he had helped many of them when they were newcomers. Monk Isa Çiçek, who was a cousin of Father Bedros’ wife, spent in the early 1970s long periods as guest in their home in Dasing, just 10 miles away from the city of Augsburg. When he eventually became Bishop of Central Europe in 1979 and a fanatical opponent in the fight against the Assyrian national movement, he suspended Father Bedros several times from the priesthood.

Another priest from Midyat, which Father Bedros mentions by name in an interview from 2001, Yahqo dbe Settike, accused Father Bedros along with an Austrian Catholic monk in Istanbul to the Turkish security for allegedly conducting subversive activities. The monk was Brother Joseph, and the director of the Catholic German school in Istanbul. Priest Yahqo had asked Father Bedros to ensure that his son Sabri would get admission to the Catholic school, but Sabri did not pass the entrance exam. Then the priest took revenge on his colleagues by falsely reporting them to Turks. Brother Joseph was expelled from Turkey and Father Bedros could not visit his beloved homeland for almost three decades. Several other Assyrians – both clergy who were agents of the Turkish secret services – and their accomplices among the guest workers had also reported Father Bedros to the Turkish authorities. They accused him of ”Assyrian separatism” and other subversive activities against the Turkish state. In fact, Assyrian separatism has never existed in modern times. Father Bedros was sentenced in absentia by a high security court in Diyarbakir, the same court that in 2001 held Father Yusuf Akbulut accountable for his statement that “not only Armenians had become victims of the 1915 genocide”.

But in 1995 a general amnesty was issued in Turkey and Father Bedros was summoned to the Turkish General Consulate in Munich, where he received the decision and the entire act of the canceled judgment. There the names of all those who falsely had reported him to the Turkish authorities can be found. Much later, Father Bedros (according to his interview in 2001) also received a written apology from his colleague Aziz Günel in Turkey for his false reporting of Father Bedros to Turkey. In my upcoming book I am going to show that Günel was on the payroll of the Turkish security service, and a key figure who organized the resistance against the Assyrian national movement in Sweden, Germany, Switzerland and other countries of immigration.

Father Bedros was thus an enthusiast to help his vulnerable Assyrian nation, whose most powerful organization – the church – had been infiltrated by hostile forces who acquired church leaders to create conflict among the Assyrians. This conflict has been labeled as the ”name dispute” but is basically a political tool to divide and rule, Father Bedros says in the interview from 2001. He reproduces a clear example of church leadership duplicity when he talks about the Patriarch Yakub’s visit to Germany in 1977. Already in 1971, the Patriarch and the accompanying bishops – including the current Patriarch Zakka Iwas – have been guests in Father Bedros home in Germany. They baptized his newborn son Ashur without protesting against the choice of this name, which they later fought eagerly. Interesting enough, the current Patriach Zakka Iwas himself was given the name Sanharib (King of Assyria 705-681BC), which he still is keeping in his ID-card.

But in 1977 the Assyrian movement gained ground among the Assyrian immigrants in the West and Assyrian associations began to emerge rapidly. Regimes in the Middle East, including Turkey, saw this as a threat. At the same time the leadership of the church felt its mundane power threatened by the secular nationalist movement. For this reason various Assyrian church leaders collaborated willingly with and got recruited by these regimes while the struggle took an organized form in the church’s auspices. The church encouraged thereafter different Assyrian tribes to resist the Assyrian movement. When Patriarch Yakub came to Sweden and Germany on his visit in 1977, he was prepared to banish the leaders of the Assyrian side in the so-called name conflict. Father Bedros says in the interview that he was present when both Assyrian representatives and their opponents, among them clan leaders, met with the Patriarch. They conversed with Patriarch separately and Father Bedros witnessed firsthand how the patriarch threw fuel on the fire by playing a false game. To the Assyrians, he said that they were educated and enlightened. They should not care about ignorant clan leaders. When he met with clan leaders, the Patriarch said that the Assyrians were parasites who were out to divide the people and harm the church. Following these meetings, Father Bedros asked a reasonable question to his patriarch: “Which side do you want me to follow? The patriarch responded with silence”, he says.

This is only one concrete example of the great duplicity of church leadership that has deepened divisions within the orthodox community. Current Patriarch Zakka has continued its predecessor’s tracks but went one step further. During Patriarch Yakub’s time the church was an intact organization. Now even the church has been torn by internal splits. The Patriarch himself has done his best to facilitate the split in the Syrian Orthodox Church by consecrating new bishops at the assembly line and establish new dioceses in the existing ones, both in Europe and in other parts of the Western world, where Assyrians of Syrian Orthodox Church affiliation live.

In the early 1980s, Father Bedros became the only priest in Central Europe who refused to accept bishop Isa Çiçek’s unchristian treatment of the Assyrian side. Bishop Çiçek made common cause with his episcopal colleague in Sweden Aphram Abboudi. The two decided to interpret the General Synod’s decree of November 1981 arbitrary and decided to abandon all who were members of an Assyrian association from any ecclesiastical services such as baptism, marriage or burial. Even elderly parents were refused holy communion at festivals like Easter.

The Bishops demanded that everyone should sign a paper where he renounced membership in an Assyrian association[2]. The Assyrian side refused of course to sign such a document and thus risked being left without spiritual services. It was then that Father Bedros in Germany and two other brave priests in Sweden stood up and defied their superior bishops. The others were Father Mounir Barbar in Stockholm and Father Issa Naaman in Västerås. The latter passed away in 2003. These three priests argued that the treatment of the Assyrian faction was against Jesus’ true teachings and made sure that the Assyrian side was not without ecclesiastical services.

Upon successful opposition from the united Assyrian front the leadership of the church backed down and the Synod decided in 1983 that all members were welcome to enjoy the church services. The only condition was that those who profess to the Assyrian or Aramean ethnicity were not allowed to become members of a church board. But in practice, only the Assyrian church members were held outside local boards. Members of the Aramean associations could freely operate in the church domains, since they felt the support of influential bishops, led by Bishop Yuanna Brahim in Aleppo[3]. Curiously, the decree of the General Synod from November 1981decided to accept only the term Syrian for the church, the people and the language. But over the past decades, several churches openly hung up the Aramean organisation’s flag in their premises, without any reaction by either the Patriarch Zakka Iwas or the Synods.

The Assyrian community is still fragmented into various factions fighting one another. Since centuries they are also divided into different churches. Father Bedros was very aware and resentful of this division. As an answer to Jan Beth-Sawoce’s question, whether he thought that the Assyrians in the future would be able to establish their own state in order to survive as a nation, Father Bedros answered that the various Assyrian churches must unite first. Otherwise it will be difficult. He therefore called for unity within the seven churches of the Middle East that has Assyrian roots, known as Syriac-speaking Churches: the Syrian Orthodox Church, The Assyrian Church of the East, The Old Church of the East, The Chaldean Church of Babylon, The Syrian Catholic Church, The Melkite Church (Greek Orthodox) and Maronite Catholic Church along with the various Protestant Assyrian Churches.

But the church leaders in these churches will not seek Assyrian unity voluntarily, unless a strong demand comes from parishioners, says Father Bedros in a voice to posterity that will forever jingle in our ears, although he himself has left the worldly life. May his soul rest in peace!

Augin Kurt Haninke

Journalist

For an AssyriaTV Assyrian language interview I conducted with three early pupils of Malfono Bedros; Aziz Hawsho, Abdulmesih Barabraham and Jan Beth-Sawoce, visit here.

[1] Malfono is ”Teacher” in Assyrian

[2] Admittedly, it was also formally included membership in any Aramaic association. But it was just a diversion. The goal was only the Assyrian faction, which also turned out in practice. The reason that even the term Aramaic was included was the General Synod’s decision in November 1981 to accept no other names but Syrian, in our own language suryoyo or Suryani in Arabic.

[3] This bishop was kidnapped on April 22, 2013 outside Aleppo together with his Greek Orthodox colleague Paul Yaziji. Their fate is unknown at this writing.

Hej!

Varför gör ni inga program längre har verksamheten slagit igen eller är Rohyo för upptagen med Assyriska FF? Ni har många frågor som måste belysas. Hur vi i diasporan och assyrierna i hemlandet ska mobilisera oss när det gäller Nineveh provinsen. Dowronoyenas fortsatta propaganda i Suroyo tv och dess attack mot ADOS högkvarter.

varför har ni tystnat?